TCU Women of WWII

TCU women prior to World War II focused on academics, hosting social events, and appearing feminine. However, as WWII approached, a new view of TCU women shifted the focus on appearance and domestication to a new “college gal bent on becoming a tycoon.”[i] Along with the war came new expectations for women to take on some of “men’s” responsibilities while they were fighting overseas, which created a balancing act of being fit, tough, and ready to fight while maintaining their femininity and poise.

Women’s shifts in attitudes, interests, involvement on campus, and appearance left men feeling threatened, especially when “coeds invading manhood’s last stronghold- his manner of dress.”[ii] Women chose to dress less “feminine” by wearing pants and button downs, instead of the traditional dresses or long skirts that had been worn to show the fluidity of the female silhouette. American females, even college girls, during WWII were expected to dress in this manner, which exemplified the “feminine” style of dress and acted as the uniform for the domesticated homemaker woman.[iii]

Despite clothing changes, society “persuaded [women] to take action focusing largely on roles that allowed them to remain feminine…women’s traditional gender roles were always highlighted for their future value when America’s soldiers returned from war.”[iv] For example, women were urged to become nurses, instead of doctors, because it allowed them to maintain their femininity while holding a career. Also, propaganda posters for factory jobs used attractive women as models to maintain a certain appearance even while working in difficult conditions.[v]

As the war progressed, women on campus were provided more opportunities to support and participate in the war effort, as the War Production Board extended defense training to women “on a basis of equality with men.”[vi] TCU students endorsed the government planned program along with the two-part coed physical education program consisting of “three hours of sports, and two hours of volunteer work weekly.”[vii] While staying physically fit and prepared to be called to action, women in the physical education program were also taught “new poise and confidence.”[viii]

Enrollment into Home Economics courses increased by seventy percent, as the department added two courses: Food Conservation and Consumer Problems. These courses further encouraged traditional gender roles by teaching women personal economics and consumer conservation during wartime. [ix] Women had been expected to be attractive, educated, aware, and more independent, but also to continue to care for the needs of the rest of their family and country.

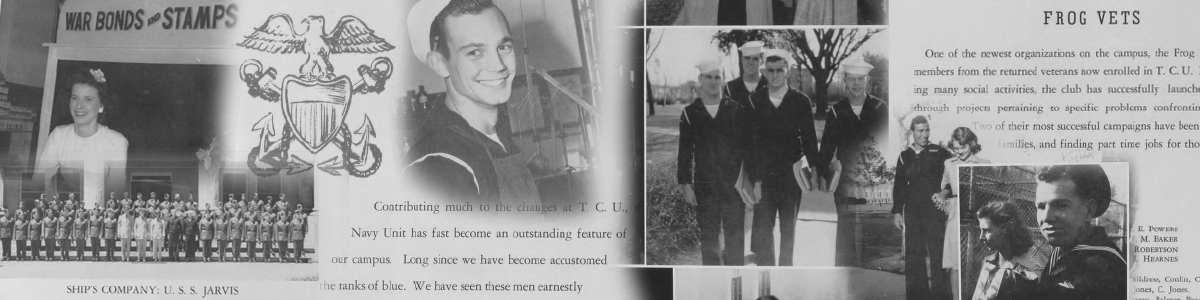

TCU women continued making their presence known throughout wartime by forming business clubs, participating in sports and defense trainings, making up the majority of the graduating classes, and returning to school after serving time overseas. Specifically, four girl veterans attended TCU on the G.I. Bill in 1945, but wished they were back in the Army.[x] Even with noticeable changes, TCU women faced conflicting role expectations: to be beautiful and dainty, yet physically fit for wartime duty, while also being domestic and responsible for their family while juggling their career. TCU women during WWII fought to break societal barriers, setting the standard for today’s empowered female TCU students.

Curator: Taylor Kandris

[i] Bill Haworth, “39 Coeds Favor Business, Music; Home Ec Is Out!”, The Skiff, November 10, 1939, 5, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, TCU.

[ii] V. G. Smylie, Jr., “Are You Man or Miss?”, The Skiff, November 1, 1940, 2, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, TCU.

[iii] Martha L. Hall, Belinda T. Orzada, and Dilia Lopez-Gydosh, “American Women’s Wartime Dress: Sociocultural Ambiguity Regarding Women’s Roles During World War II,” The Journal of American Culture 38, no. 3 (September 2015): 232-242.

[iv] Mary Weaks-Baxter, Christine Bruun, and Catherine Forslund, We Are a College at War: Women Working for Victory in World War II (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2014), 91-92.

[v] Weaks-Baxter, Brunn, Forslund, We Are a College at War, 92.

[vi] Beverly Wade and Mary Allene Jones, “Defense Training Courses Extended to Admit Women,” The Skiff, February 27, 1942, 1, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, TCU.

[vii] Wade and Jones, The Skiff, 2.

[viii] Wade and Jones, The Skiff, 2.

[ix] Margaret A. Ramage, “New Interest in Home Economics Due to War Conditions,” The Skiff, February 27, 1942, 4, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, TCU.

[x] Bobbye Rheinlander, “Four Girl ‘Vets’ in T.C.U. on G.I. Bill of Rights,” TCU Skiff, December 14, 1945, 4.

For Further Reading:

Emily Yellin. Our Mothers’ War. (New York: First Free Press. 2005).

Yellin’s book discusses specific examples of women and their roles on the home-front during World War II. These roles and jobs include running their family homes, working in factory jobs, working overseas, providing medical assistance as nurses, and even some volunteer services, such as the Red Cross.

Maureen Honey. Creating Rosie the Riveter: Class, Gender, and Propaganda during World War II. (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press. 1985).

Honey examines media, particularly advertisements, to show how propaganda influenced women’s involvement in the war efforts during World War II. Propaganda during WWII used beautiful women as models of how to dress feminine while working in tough conditions. It was also used to appeal to women seeking independence and a meaningful life.