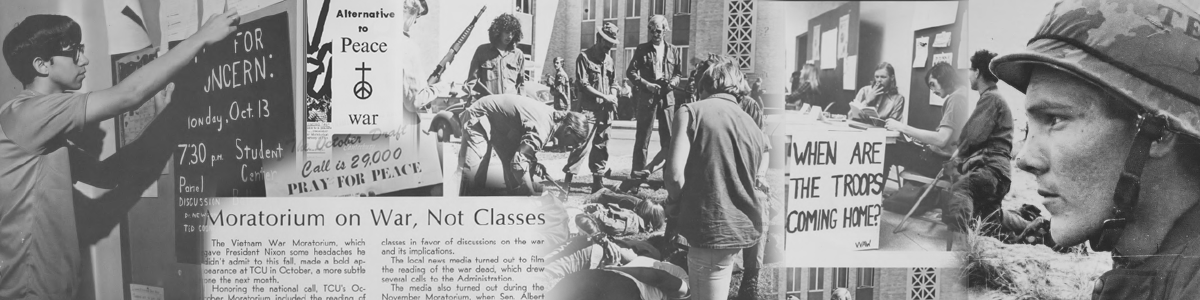

Anti-War Demonstrations at TCU

During the Vietnam War, students across the nation engaged in radical, and sometimes violent, anti-war demonstrations. However, at TCU, the prevailing attitudes were much more favorable toward the Vietnam War. This pro-war attitude stemmed from a distinct regionalism, which had led southerners to support war involvement throughout American history.[i] The majority of those at TCU held these ideals; however, the left-leaning nature of TCU’s Brite Divinity School prompted its students to view the war much differently than most of campus. Even though they represented a minority, anti-war demonstrators impacted the TCU and Brite campuses throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Student Activities Advisor and later Vice Chancellor Dr. Donald Mills describes the anti-war demonstrations at TCU as more moderate and tame than what took place in other parts of the country. Perhaps the most radical of the anti-war activities took place in spring 1968 when someone placed a makeshift bomb on the ROTC building and started a small fire.[ii] One of the largest demonstrations against the war was the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam. On October 15, 1969, TCU students gathered to mourn those killed in Vietnam and encourage debate.[iii] On a different occasion, one student displayed his opposition to the war in a more unique way. As the ROTC presented itself to a visiting military general, the student purposefully walked through the demonstration wearing a shirt that read “Fuck War.” TCU police removed the student, and he was taken to Vice Chancellor Howard Wible’s office, where the vice chancellor told him to remove the offensive word on his shirt. So, the student proceeded to mark out the word “War,” demonstrating his point that the war was what was offensive, not the obscenity.[iv]

While the actions of the TCU administration reflected their pro-war leanings, Brite Divinity School displayed its opposition to the war on several occasions. Some students enrolled in Brite specifically to avoid the draft through student deferments, a trend on par with the national estimate that college attendance increased by four to six percent throughout the 1960s.[v] Several Brite faculty members also held draft counselling sessions to inform students of their legal options if they were conscientious objectors.[vi] Those subject to the draft were also more likely to favor immediate withdrawal from Southeast Asia.[vii] A few students displayed this sentiment by burning their draft cards on campus.[viii]

The prevailing attitude at TCU during the 1960s and early 1970s was pro-war. Still, some students displayed their opposition in meaningful ways. Most demonstrations on campus were tame, although their presence was visible, even if only representative of a minority. In this way, the campus displayed several of the aspects of the protests that impacted universities across the United States, yet it still reflected the predominant southern ideology of the time.

Curator: Andy Mills

[i] Joseph A. Fry, The American South and the Vietnam War: Belligerence, Protest, and Agony in Dixie (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2015).

[ii] Donald Mills, interview by Andy Mills, November 2, 2017.

[iii] Johnny Livengood and Joe Kennedy, “War Protest on Campus,” The Skiff, October 17, 1969.

[iv] Mills, interview by Mills, November 2, 2017.

[v] Mills, interview by Mills, November 2, 2017.; David Card and Thomas Lemieux, “Going to College to Avoid the Draft: The Unintended Legacy of the Vietnam War,” The American Economic Review 91, no. 2 (2001): 97-102.

[vi] “Campus Ministry Offers Counseling For Draft-Wary,” The Skiff, February 2, 1971.

[vii] Daniel Bergan, “The Draft Lottery and Attitudes Towards the Vietnam War,” Public Opinion Quarterly 73, no. 2 (Summer 2009): 379-384.

[viii] Mills, interview by Mills, November 2, 2017.

For Further Reading:

Jeffery A. Turner, Sitting In and Speaking Out: Student Movements in the American South, 1960-1970 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010).

Sitting In and Speaking Out: Student Movements in the American South, 1960-1970 by Jeffery A. Turner discusses student movements across the southern region of America. It explains how these protests escalated throughout the 1960s from a southern perspective that was rooted in race.

Melvin Small and William D. Hoover, Give Peace a Chance: Exploring the Vietnam Antiwar Movement (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1992).

In their book, Give Peace a Chance: Exploring the Vietnam Antiwar Movement, Melvin Small and William D. Hoover consider contentious issues in the Vietnam War peace movement, that impacted students and protestors of all types. They go in depth into disagreements between feminist groups, military reformers, and student organizations, despite their similar goals for the nation.