Counterculture at TCU

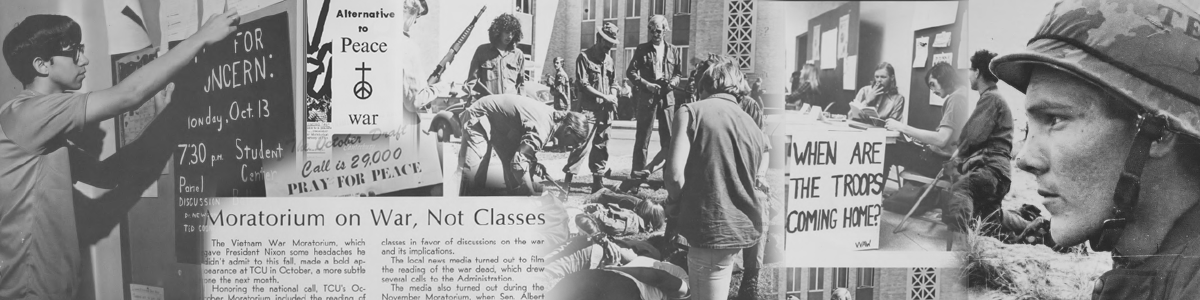

As the Vietnam War raged it brought about a radical counterculture that took hold of college campuses and brought a wave of new attitudes challenging social norms. Texas Christian University was no exception when it came to the effects of counterculture on college campuses.

In September 1966, Psychology Professor Dr. Charles Bridges decried campus conformity. He connected the lack of differences in student political ideology to the majority of students coming from the same upper-middle class background.[1]

Nonetheless some TCU students did have varied political ideologies. In August 1969 Jim Harrison, Steve Stewart, Brian Black, and Billy Yarborough published an underground student magazine called Spunk Comes Naked, to establish social change on TCU campus by targeting specific social issues. They worked to achieve this goal by bringing students together from different political and social backgrounds to give their uncensored student opinions. Their staff description makes this clear: “Our staff comprises an equitable balance of all facets of TCU society. We have Greeks, Catholics, Blacks, Athletes, Artist Protestants, Whites, Conservatives, Scholars, Dunces, Liberals, Independents and VIRGINS”.[2]

Within two days of Spunk Comes Naked’s release, Chancellor James Moudy called an urgent meeting with the magazine’s faculty advisors and student editor, Peter Fritz to discuss the cover image of four nude men, facing a nude sitting female. While Chancellor Moudy viewed the image as a plot to sell magazines, Fritz intended to stir the student body’s reaction. In agreement, minor changes were said to be done to the Spunk, which never actually came to be. [3]

The second edition, All I said was Spunk was released in the spring of 1970, by a reshuffled batch of students, self-described as “a dirty-pinko hippie-infested-dope utilizing hoard of misfits trying to remark that which we cannot understand”.[4] Taking a more radical approach to expressing their opinions on social issues, they publicized editorials such as “Blackman in U.S.A, Sexism, and the Black Dictionary”.

Due to the Spunk’s aggressive stance, chief editor John Checki refused to show copies of the magazine to the Publication committee because he felt they would attempt to censor Spunk. His refusal to show the committee was a violation of the magazines policy and procedure charter. As a result on April 1970, the Student Publications Committee halted production of the Spunk magazine.[5]

Counterculture thrived on college campuses, affecting each individual differently. Texas Christian University allowed for individuals of varied backgrounds to come together to have their opinions heard.

Curator: Jon Ortiz

[1] John Miller, “Psychologist Decries Campus Conformity”, The Skiff, September 23, 1966, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University

[2] Spunk Comes Naked, August 30, 1969, Spunk, Vertical Files, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[3] Michael V. Adams, Spunk Comes Naked, The Skiff, September 2, 1969, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University

[4] All I said was Spunk April 8, 1969, Spunk, Vertical Files, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[5] “Spunk ‘Forgets’ Advisers”, The Skiff, April 14, 1970, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University

For Further Reading:

Kenneth J. Heinman, Campus Wars: The Peace Movement at American State Universities in the Vietnam Era. (New York City: New York University Press, 1993)

Campus Wars: The Peace Movement at American State Universities in the Vietnam Era by Kenneth Heineman discusses the unknown story of anti-war activism at state schools during the 1965 to 1975. Opposing traditional narrative that campus activism occurred at elite schools such as Berkeley

Martha Biondi, The Black Revolution on Campus. (Berkely University of California, 2012)

The Black Revolution on Campus is an account of the forgotten chapter of the black freedom struggle. In the late 1960s to the early 1970s, Black Students organized hundreds of protest that sparked crackdown, negotiation and reform that transformed college life.