Paul F. Boller, Jr: An United States Navy Japanese Translator

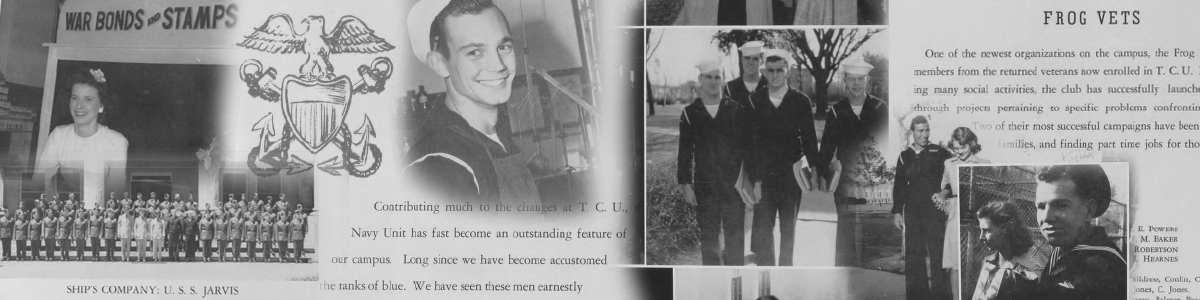

Paul F. Boller, Jr. was born on December 31, 1916 in Spring Lake, New Jersey. His childhood consisted of intellectual conversations with his family, which played an integral part of his future.[1] Boller graduated as class valedictorian from Yale University in 1939, then joined his friend in enlisting in the Navy.[2]

Knowing he was not physically fit to fight for the Navy, he instead chose to study at the Navy’s Japanese Language School. His academic resume proved that it was the perfect match for Boller because only the smartest got to study at the Japanese Language School. A majority of the selected college graduates had six months of Japanese or Chinese language study. Some exceptional cases, like Boller, if they graduated with Phi Beta Kappa honors, were eligible for the school.[3]

For the students, their goal was to understand 1,600 commonly used Japanese characters, to translate and understand different Japanese newspaper articles on different subjects, and to converse semi-fluently with a focus on frequently used naval and military terms.[4] These translators played a lesser known, but critical role during World War II. After about eight months to one year, the translators were split between the Marines and the Navy.[5] Boller was chosen for the Navy.

After spending time with many Japanese professors at the Japanese Language School, Boller—like other students—found the Japanese to be their friends.[6] Boulder, a conservative city, opposed this group of Japanese people moving to Boulder, so it was difficult for the professors to make friends outside of the school.[7] Therefore, their students became their friends. Compared to the soldiers’ belief that the Japanese was the enemy, the translators befriending the Japanese set them apart. The memories of the translator’s Japanese friends from the school helped the translators treat the Japanese prisoners they had captured more respectfully. The translators would earn the prisoners’ trust to get information from them instead of using brute force.[8]

Originally, Boller got the assignment to go with the troops to Iwo Jima, but at the last minute, got reassigned to the translating team at the Naval Intelligence Center in Guam.[9] While there, the U.S. military constantly bombed Japan. Remembering that Japanese civilians were human and helpless, Boller and an intelligence officer enlisted the help of Japanese POWs to create pamphlets to be dropped over the cities that were going to be bombed.[10] Boller wanted to warn the civilians in these cities because he did not believe that it was right for innocent people to die during bombing attacks.

In 1955, he was honorably discharged by the Department of the Navy.[11] Boller earned his Ph.D. at Yale, and then became a professor. He taught at Southern Methodist University, the University of Massachusetts, Boston, and finished his career at Texas Christian University. At TCU, Boller enjoyed giving lectures about his research on the American presidents.[12] After his retirement, he kept in contact with friends he made in Japan, and even went back to visit before his death.[13]

Curator: Amanda Ogata

[1] Paul F. Boller, Jr to Mom, 1942, Folder 9, Box 8, Records of Paul F. Boller, Jr., Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.; Kenneth Stevens, interview by Amanda Ogata, October 19, 2017.

[2] Stevens, interview by Ogata, October 19, 2017.

[3] Paul F. Boller Jr to Family, 1939, Folder 9, Box 8, Records of Paul F. Boller, Jr., Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[4] Roger Dingman, Deciphering the Rising Sun: Navy and Marine Corps Codebreakers, Translators, and Interpreters in the Pacific War (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2009), 13-14.

[5] Dingman, Deciphering the Rising Sun, 60.

[6] Dingman, Deciphering the Rising Sun, 120.;“Words at War: The Sensei of the US Navy Japanese Language School at the University of Colorado, 1942-1946,” Discover Nikkei, April 10, 2008, accessed November 3, 2017, <http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2008/4/10/enduring-communities/>

[7] Paul F. Boller, Jr to Family at Boulder, 1940, Folder 9, Box 8, Records of Paul F. Boller, Jr., Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[8] Dingman, Deciphering the Rising Sun, 120.

[9] Stevens, interview by Ogata, October 19, 2017.

[10] “Paul F. Boller, Jr.: 1916-2014”, American Historical Association, accessed November 2, 2017, <https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/october-2014/in-memoriam-paul-f-boller-jr>

[11] Honorable Discharge from the U.S. Naval Reserve, 1955, Folder 9, Box 8, Records of Paul F. Boller, Jr., Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[12] “Paul F. Boller, Jr.: 1916-2014.”

[13] “Paul F. Boller, Jr.: 1916-2014.”

For Further Reading:

James C. McNaughton, Nisei Linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service during World War II, (Military Bookshop, 2007).

This book tells the story of Nisei (second generation Japanese) linguists in the Army’s U.S. Military Intelligence Service. It explains how the Army recruited these ethnic minority soldiers, and how they were trained in secret to use their ethnicity to America’s advantage.

Sandra Vea, Masao: A Nisei Soldier’s Secret and Heroic Role in World War II, (DMA Books, 2016).

This book tells the story of Masao, a Japanese-American soldier who was secretly recruited into the Military Intelligence Service. It explains his experiences of looking like the Japanese enemy, and how he had to earn the respect of the U.S. soldiers because he was Japanese.